by Andrew R. Basso & Andrea Perrella

Why has Reconciliation in Canada stalled? What barriers exist to the implementation of transitional justice? Sometimes the simplest questions can yield the most important findings. That is certainly the case for our multi-year study of settler public opinions towards Reconciliation and Indigenous peoples.

We understand a settler as anyone who does not self-identify as Indigenous and is not recognized as a member of an Indigenous nation by that nation.[1] We chose to study settlers specifically due to their powerful and privileged positions in Canadian society. This over-empowerment is intended result of centuries of developing matrices of settler colonial control in what is now Canada. As political actors, settlers wield an incredible amount of political sway and can choose to accept the need for Reconciliation, as called for by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) or choose to disregard calls for fundamental justice for Indigenous peoples as yet another frivolous minority rights issue that can be brushed aside.

Guided by genocide studies literatures, we found that denial has been classically understood as the final stage of genocide. Recent innovations suggest that denial is also part-and-parcel of atrocity programmes whereby perpetrators create obfuscated worlds to justify their actions. Canada has such a genocidal past – the Indian Residential School (IRS) system (1830s-1997) – as uncovered by the TRC and this history sends incredible ripple effects to the present day. Colonial violence in Canada is not limited to the IRS system, though, and also includes the similar Day School system, disease and starvation to clear the plains, forced sterilization programs, Sixties and Millennium Scoops, domicide and the destruction of Indigenous homes, and intense segregation and pauperization of Indigenous nations and peoples. Amidst this backdrop of atrocity and repression, Canada has much to answer for. The IRS system is one of the most important processes for which to make amends. When denial is allowed to continue, cycles of violence remain opened and paths to justice are closed. Thus, denial is a potent barrier to justice that must be overcome for Reconciliation to succeed.

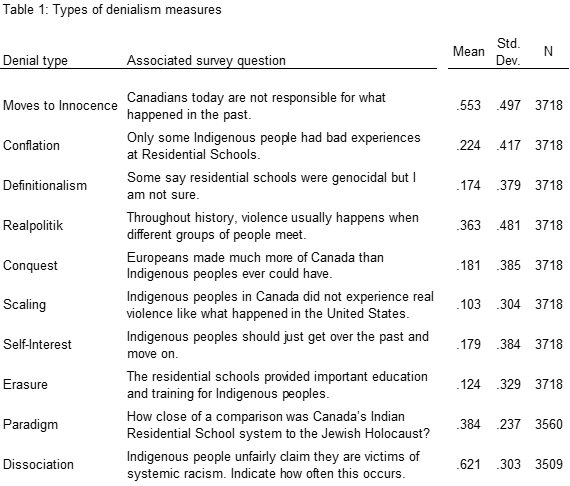

As part of our wide-ranging study, where denial is but one piece of the puzzle, we investigated unique types of genocide denial offered by some settlers to prevent justice for atrocity and tested for their prevalence among survey respondents. Our research uncovered ten types of denial in Canada (visualized in Table 1 below). All ten types can be shown to be demonstrably false through careful interrogations of history and its reverberations across space and time, but the problem remains: what is the prevalence of these beliefs among settlers? If denial is prevalent, Reconciliation will almost certainly not succeed as it cannot even take flight. If denial is not prevalent, Reconciliation at least stands a chance as barriers to justice have been removed.

Across three waves of national, online, opt-in surveys administered from 2021 to 2023, we have totaled nearly 4,500 respondents and new understandings of settler Canadians’ understandings of the past and how it connects to the present. Survey participants offered responses based on a Likert scale.

For the questions in Table 1 and the test of Dissociation, the higher the mean, the higher the level of agreement with the statement. Regarding Paradigm denials: the low level of agreement means that respondents do not believe the IRS system is comparable to the Holocaust. Importantly, ordinally scaling suffering like this is generally viewed as illegitimate in genocide studies canon.

As Table 1 shows, generally few respondents agreed with denialist sentiments. Many survey respondents rejected the ten denialist sentiments. This may suggest that Reconciliation-oriented public education efforts have had demonstrable effects in overcoming potential genocide denials. In this sense, we can confirm that transitional justice in Canada is possible as settlers do not generally reject accurate understandings of IRS genocide. However, four other important implications emerge from this aspect of our study.

First, survey respondents did, unfortunately, strongly agree with “dissociative” denialism and “moves to innocence”. It is troubling that in light of years of truth telling and experience sharing, a majority of settlers believe Indigenous peoples unfairly claim that racism exists in Canada and that Settlers today do not want to take responsibility for the past. These two types of denialism should be combatted with targeted public education efforts to make settlers better understand connections of the past to the present and to help them believe the experiences of Indigenous peoples.

Second, along demographic lines, average levels of denialism are higher among males, those who reside in the three Prairie provinces, and those whose education is less than a high school diploma. However, the differences are not always very pronounced. Thus, denial exists across different Canadian demographic sectors and is not always easily predictable.

Third, no study has ever postulated on what levels of denial form barriers to justice. We are thus concerned that while our findings demonstrate many settlers do not agree with statements concerning genocide denial in Canada, any level of denial could potentially derail transitional justice efforts. This requires significant more comparative quantitative and qualitative research in the future.

Fourth, utilizing insights from other parts of our study, we can confirm that overcoming denial does not necessarily mean an automatic recognition of past wrongs. To recall: denial is a mechanism one can engage to prevent acting on new information. More specifically, genocide denial is the final stage of violence and a barrier to justice. Recognition, on the other hand, is an active first step towards justice where one accepts historical realities, their meanings for acting in the present, and the beginning of building a more just future.

On this third annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, it is important to reflect on progress made and progress yet to be achieved. This reassuring fact may open opportunities for justice to occur. However, implementing transitional justice programs in settler colonial contexts where violence is often structural is a difficult task. It is up to settlers to ensure elected representatives keep Reconciliation and treaty promises as we are all inheritors of Canada’s past, occupy its present, and craft its future with our decisions and actions daily. Minimally, according to our research, many settlers reject statements of denial meaning justice may be possible. Fundamental justice, however, does not stop with overcoming denial. The latter is just the starting point.

[1] It is important to recognize that some peoples were forcibly brought to Canada through violent processes like the institution of slavery and these people may not identify as settlers.