Just what an election is about is a question at least as important as who is standing. Because most voters don’t have coherent ideologies, but rather many different attitudes, a candidate might be better off making an election about something good if you’re the incumbent (e.g. a recent uptick in unemployment) or about something bad (e.g. a scandal looming inside the incumbent party). Politicians go to great lengths to frame the ballot issue. We went into this at some length here.

The problem for political leaders in a democracy (or maybe even autocracies, for that matter) is that it’s not always up to them to decide. There’s heavy competition. One the one hand, in multi-party democracies, other parties try to make the election about something. Voters, on the other hand, might actually have their own priorities. And between the two are a group of pesky professionals we know and love, the journalists. One part citizen, one part objective observer and one part political actor in their own right, journalists and their editors make decisions all the time about what they should cover. At one level, covering an issue a lot, communicates to voters that that issue is important. This is the famous agenda-setting power of the news media (McCombs and Shaw 1972).

As part of our ongoing analysis of the 2022 Ontario election, LISPOP gathered news stories from 29 different daily newspapers from across the province, as well as the Canadian Press. We searched for articles that had the names of any of the Ontario political parties, or their leaders as well as the words “election” or “campaign”.

We imported the text of each article from a database of newspaper articles and constructed issue dictionaries for several political issues. These were: the COVID-19 pandemic, housing, jobs, debts and deficits, health care (non-COVID related), the environment, jobs and inflation.

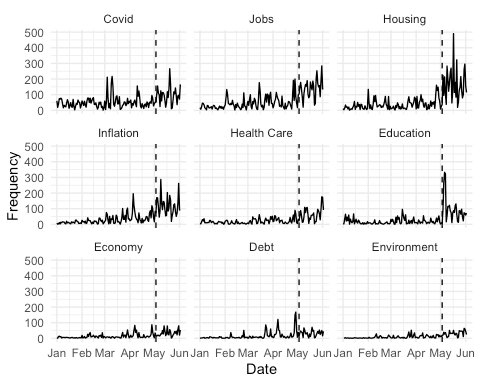

The idea here was to measure what journalists were writing about. The raw results are in Figure 1. The graph shows raw counts of each of the terms that we used to compose our dictionaries by date.

A few things stand out. First, note the spike in references to COVID-19 in March of 2022. There was in fact an increase in COVID-19 as measured by the provincial government that month, plus, the province announced that mask mandates were to be lifted that month. But more importantly, as soon as the election started, journalists added to the issue mix, reporting extensively on housing, jobs and inflation.

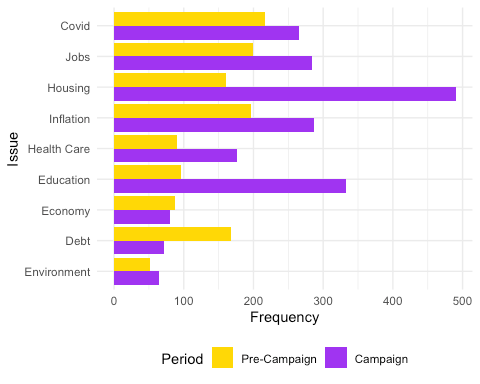

We can more easily compare the issue agendas by grouping them into pre- and campaign period counts like in Figure 2.

It’s probably worth noting that journalists did not stop covering COVID-19, it’s just that they started covering issues like inflation, jobs and housing prices a lot more.

There’s a lot at stake in this. People critical of the Ford government’s handling of the pandemic were frustrated the government was returned and that the opposition parties never seemed to hold the government to account for perceived failures. These data do suggest that the media largely moved onto other issues. It’s another thing as to whether this was in spite of, or because of, what voters wanted. We’ll look at that in a next blog post.

This research could not have been done without the outstanding assistance of LISPOP’s RA Rafael Campos-Gottardo. Follow him on Twitter!